To treat or not to treat for verroa mites is a big discussion….even bigger is the type of treatment to use. Opinions and judgement run high when a group of beekeepers have this discussion. Some feel that any treatment is a foul against nature, others take it as just part of what it takes to successfully raise bees. The good news is that you get to choose for yourself how you work with your bees. The point that I want to make is that you need to know your options before you can make an informed decision. Choose what is good for you and don’t get too judgy about what others are doing.

Hopguard® II revisited

By Dr. Elina L. Nino, Extension Apiculturist. UC, Davis, reprinted from the current newsletter

Every time I talk to beekeepers here in CA, I hear, “Boy do I wish we had more options for

treating Varroa”. Well, the good news is that this February, California has re-approved Section 18

emergency use of Hopguard® II. Eric Mussen has briefly written about this product in the past,

but a couple of papers that came out last year have prompted me to revisit this topic. Hopguard®

II is basically an “old” product developed by BetaTec Hop Products Inc (developed in

Washington state – Editor) but it has an improved delivery system. The active ingredient is the

Potassium salt of hop beta acids at 16% and yes, these are the same hops you would use for

making beer.

Hopguard® II can be applied to both packages and colonies and since it can’t reach the mites

on brood, the suggested timing of the treatment is when there is minimal brood in the hive so the

mites can’t “hide”. It sounds to me like packaged bees might be an ideal time to treat. If your bees

are already in a hive try to treat early in the season when the brood is just building up or late in

the fall when brood starts tapering off (BUT don’t wait too long as you don’t want your colonies

to succumb to Varroa).

2- or 3-lb packages should be treated by attaching 3 half strips inside a package so they hang

from the top and should remain in the package (with bees, of course) for at least 48 hours. Hives

need to be treated at a rate of 1 strip per 5 frames covered with bees and the treatment should only

be applied in a BROOD CHAMBER. The strips are easy to apply. Just hang them over a frame in

the middle of the brood box. If using 2 strips, the other strip should be placed on a neighboring

frame but 4 inches away from the first one.

Now just a couple of cautionary notes. Even though the product is safe to use during nectar

flow, DO NOT apply it in the honey supers. And please don’t be tempted to use honey or wax

that is in the brood chamber! If the bees do not remove strips after 30 days, you should remove

them from the hives. Hopguard® II can be used up to 3 times per year but it shouldn’t exceed a

total of 6 strips per year per colony (including package and hive application). You need to wear

chemical-resistant gloves when you’re working with the strips and since the material is pretty

sticky you’d probably want to wear them anyway.

So how do all these recommendations fare in the real world? A study by DeGrandi-Hoffman

and colleagues (2014) investigated the effect of Hopguard® on Varroa counts in commercial

colonies established from packages or splits. They used a mathematical model to determine the

timing of Hopguard® applications and at the end they compared Varroa counts predicted by the

model and what they actually found.

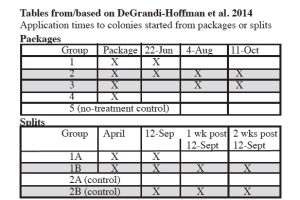

To show the timing of the applications I thought it would be best to do this in a table, so here

you go:

All of the mite counts were done with a sugar-shake method and reported as # mites/100 bees.

For packaged bees, the final mite counts were done after the October treatment and significantly

lower mite counts were recorded for groups 2 and 3. For colonies made from splits, the lowest

mite counts in November were recorded in groups 1B and 2B.

Interestingly, the model predicted a much more effective mite knockdown by the fall than what

was actually seen in the field. The authors hypothesize that these difference might have been due

to various other factors not taken into account by the model or various model parameters not

following what was recorded in the literature, underestimation of initial mite population numbers,

and/or a suboptimal mite removal during sugar-shakes.

So it seems that the most effective mite knock-down was in colonies that received 3 or 4

treatments during the year and particularly important were the late season applications. I do want

to remind you that the California regulation for Hopguard® II states that no more than 6 strips per

colony per year may be used. Because of this you might want to stick with one initial application

earlier in the season and two later in the season if starting from packages, or, if you are splitting

your colonies, you should be able to get away with 3 consecutive applications towards the tail end

of the season, although I would have liked to see the authors take another mite count the

following spring and record colony mortality.

The results of this paper also highlight the importance of using the product when there is no or

little brood or for 3 consecutive weeks to cover the entire brood cycle. Drift between colonies

might play a role in increasing mite numbers in a particular hive. And while you can’t control

what your neighbor does, you should make sure you treat all of your colonies that need the

treatment.

Another word of caution — you don’t want to wait until your mite populations absolutely

explode in the hives in order to treat. A possibility would be to follow an IPM approach by

applying a different miticide around Hopguard® II or, if you have fewer colonies, try utilizing

physical or mechanical control such as use of screened bottom boards, drone comb removal or

creating a break in brood cycle by caging the queen or splitting your colonies. Going with Varroa

resistant/tolerant honey bee stock is yet another possibility so think about it when you’re

purchasing your next batch of queens.

The last thing I wanted to mention is a study by Vandervalk and colleagues (2014) that found